“He was a fabulous singer; he could sing the blues better than anybody I’ve ever heard. He had the timing, the phrasing, a fabulous voice… he was just great.” – Donnie Walsh

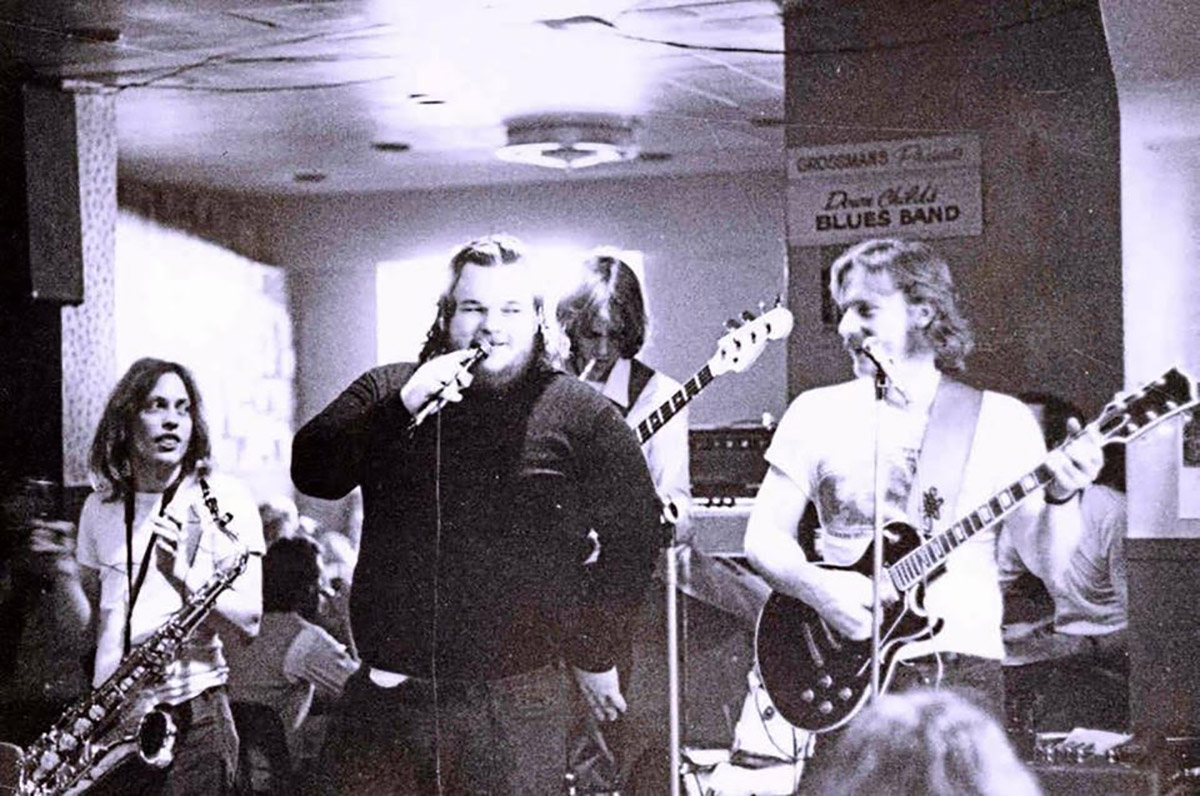

So I’m looking at this picture. Here’s Donnie Walsh and his brother, Richard — Downchild’s first vocalist and the co-founder of what has been Canada’s best blues band for 50 long years. Don’t know who took the shot, or when, but maybe 1974.

These are the original blues brothers.

Mind you, nobody ever called Richard Walsh Richard; he was always “Hock,” as in ham hock — a reference to his girth, his arm muscles, and his overall size.

To understand Hock it would help you if you’d known his Dad. Cloth-capped, small in stature, he gave both his kids their dry sense of humour. But added, for Hock, a sense of the absurd and a willingness to make an ass of himself if would get a response from the audience or the rest of the band.

Born December 1948, the brothers’ folks ran The Lakeview Inn, a resort hotel in North Bay, Ontario — and one of the kids’ greatest pleasures as they were growing up was to creep into the empty bar early on Sunday mornings and turn on the jukebox to listen to all the paid-for songs that hadn’t been played when the bartender pulled the plug at closing time.

The family moved to Toronto when the brothers were teenagers; within a year or two Donnie wanted to start a band, and was already seriously into blues. An ex-girlfriend still remembers how he’d take off whatever record was playing at a party and replace it with Jimmy Reed’s classic first album, Live at Carnegie Hall (which, in fact, wasn’t live and wasn’t recorded at Carnegie Hall.)

Naturally, his brother — who didn’t play an instrument — was the obvious choice to handle the vocals. After three months of intensive rehearsals, the Downchild Blues Band was ready to face the world.

The band’s first gig, in the late summer of 1969, was at Grossman’s Tavern, a legendary bar on Toronto’s Spadina Avenue — yes, it’s still there. Back then Grossman’s, close by Kensington Market, was an oasis for new Hungarian immigrants, West Indians, dyspeptic waiters, hippies, poets, and draft dodgers. Al Grossman, the owner and one-man welcoming host, ran a loose ship — fair enough, given his clientele. There was live music, usually provided by accordion duos and trios playing waltzes and polkas from the old country.

I never knew how the band persuaded Al to let them play, but it was certainly a musical sea change. Rough and rowdy, like the surroundings, the band found an audience — and Hock Walsh relished his new gig. Al gave the band its first cheque, made out to Don Child.

Hock’s performances were both righteous and ribald, and always reminded me of a slightly inebriated W.C. Fields, crossed with a less manic Harpo Marx. Blessed with a clown’s natural ability to turn the laughter onto himself, his introductions to songs were hilarious. He wasn’t afraid to move away from his microphone to back up against the drummer and fart. On a quiet night, with the waiter stacking chairs on tables as the band was still playing Hock improvised a 25-minute song with sardonic verses about everyone in the room, including the owner, the owner’s daughter, and the impatient waiter.

More importantly, Hock had a distinctive voice that allowed him to model his work on such classic singers as Big Joe Turner without imitating them. And the contrast between the wisecracking, rotund singer and his brother — a more serious musician and a dedicated guitarist and harmonica player — was one that helped make the Downchild’s popularity grow almost instantly.

In the late fall, the band decided to make a record — it was to be one of the very first independent releases in Canada.. Somebody, and it could have been Hock, decided to call the album Bootleg. The cover was a visual pun: a black and white shot of Hock’s scuffed army boots. At their first out of town gig, in a punch-up bar in suburban Brampton, the band sold one copy. Thankfully RCA picked up the album two weeks later and paid an advance of (if memory serves) $2,000.00. There was a party.

And, fifty years later, Bootleg still holds up pretty well. There are some well-chosen covers (and two Jimmy Reed songs), and three Donnie Walsh originals, one co-written with his brother.

Eventually, the band graduated to the El Mocambo, then the hippest joint in town and just across the road from Grossman’s. There were occasional gigs out of town (including their first out-of-province date, in Winnipeg). Hock’s stage presence and his laid-back sardonic sense of humour gave the band it’s up-front personality, and kept audiences coming back.

Every now and then, still pumped after a good gig, the band would check into one of the numerous after-hours (and illegal) drinking joints, including a famous one on Queen Street run by a local comedian, Dan Aykroyd. Usually, the band would just drink ‘til the small hours; occasionally, if the mood (and the whiskey) struck everyone, the band would play a loose set. The other night owls offered free drinks; Hock cheerfully accepted them all.

Three years after the debut album, the band recorded again — and there was a much larger audience now; the band was now touring Ontario, still playing at the good ol’ Elmo as well, and there was a pent-up demand for Straight Up. Best of all, the new record has genuine hits on it — including (I Got Everything I Need) Almost, Shotgun Blues and a cover of a classic Big Joe Turner song, Flip Flop and Fly, which nine months later became a massive hit across the country.

Hock, alas, seemed less able to handle the band’s growing fame, and its grueling, non-stop, touring schedule. Usually late for the morning departure of the tour van, he irritated other band members. On one occasion, during a late-night intervention in a motel somewhere in the Prairies, he was instructed in no uncertain terms to be on time. The next morning he showed up at the van wearing his boots and wrist watch, but otherwise dripping wet from the shower, and stark naked. Glancing at his watch he turned to the astonished band members. “Eleven o’clock,” he announced. “Let’s go.”

In 1974, Donnie fired him, finally exhausted by his brother’s fecklessness, and other singers attempted to fill Hock’s army boots.

Meanwhile, Aykroyd — late-night booze can owner and semi-unemployed stand-up comedian — got a gig on Saturday Night Live, the popular (and still ongoing) television show. Meeting fellow cast member John Belushi, the pair — with Downchild and the Straight Up album as their examples — created the Blues Brothers, first as a sketch on the show and later as a performing duo with ace sidemen like Steve Cropper, Duck Dunn and Matt Murphy.

And the first Blues Brothers album, released in 1978, has sold (so far) some seven million copies. It features two Downchild songs — including Hock’s co-write Shotgun Blues — and a version of Flip Flop and Fly. To say the arrangements are almost identical to Downchild’s would not be an exaggeration. And, yes, Joliet Jake (Belushi’s alter ego) did indeed pick up some of Hock’s vocal mannerisms.

But Hock’s connection with Downchild was not over. Briefly — perhaps to take advantage of the Blues Brothers connection — he re-joined the band, singing alongside his successor, Tony Flaim. And in 1985 he recorded another album, Gone Fishing. “Then he quit again,” said his brother.

With failing health, but with his sense of humour intact, Hock continued to sing, sitting in as a guest star with various Toronto bands. On one occasion, he marched into a club, walked directly onstage, and called the next tune, Flip Flop and Fly.

“We already played it, just before you came in,” said the bandleader.

“Ya didn’t do it right,” Hock insisted, and the band played it once again…

Hock died, alone in his apartment watching TV, on New Year’s Eve, 1999. And anyone who knew him, and those who heard the band in its early days, still misses him. And we hold his memory dear.

– RICHARD FLOHIL